Omnimoral Subjectivism: Revisiting the Boundaries of Right and Wrong

Introduction

Can the very same act be called moral in one context and immoral in another? Many traditional accounts of ethics say no: they claim a single, objective order of right and wrong applies to everyone, everywhere. However, lived experience and historical variation suggest otherwise. An action that seems self-evidently evil to one culture or individual may be perfectly acceptable, or even virtuous, to another. This striking divergence raises a key philosophical question: are we tapping into universal moral truths, or merely following local conventions, personal feelings, and subtle power dynamics?

In response to this puzzle, some thinkers pursue foundational principles, divine rules, natural law, or rational dictates, that promise universal guidance. Others look instead to cultural relativity or psychological factors. Here, we take a postmodern turn, proposing a view that morality functions as a social and subjective phenomenon, one that depends on the perspectives of those who judge. Rather than asking, “Which moral code is correct in an absolute sense?” this approach asks, “How and why do people declare certain acts right or wrong, and whose interests are served by calling them so?” The aim is not to discard morality but to scrutinize its construction, revealing how every moral pronouncement arises from within particular histories, viewpoints, and contexts.

No single philosophical tool can capture this complexity, so the discussion moves fluidly between deconstructive critique and real-world examples. Genealogical analysis, for instance, uncovers the political and psychological origins of values we often treat as timeless. Meanwhile, a game-theoretic lens shows how shifting incentives and power dynamics can turn even trivial actions into matters of right or wrong. In other words, morality emerges when and where assessor decide to see it, and their reasons, whether altruistic, pragmatic, emotional, or something else, are as varied as human experience itself.

Far from leading to nihilism, this viewpoint highlights just how deeply people do care about moral rules, even when those rules lack any transcendent foundation. Emotional attachment and social pressures can feel as binding as supposed universal commands, reinforcing norms that shape entire cultures. Yet at every turn, these norms remain open to scrutiny and change, refuting the notion of moral absolutes. Seen in this light, “omnimoral subjectivism” is an invitation to probe beneath the surface of what we call ethical truth. If morality is indeed a contested space where claims of right and wrong gain authority through social negotiation, then understanding how these claims arise and evolve is central to understanding who we are as moral beings.

This introduction sets the stage for a deeper investigation into the interplay between universalist ambitions and local realities, between claims of timeless virtue and the fluid context of human life. The discussion to come seeks not to replace one rigid system with another but to open room for thoughtful exploration, prompting a reconsideration of whether anything in ethics stands above the forces of history, perspective, and power. By reframing morality as a process of continual social construction, each case of “This is right” or “That is wrong” takes on a new significance: it becomes a snapshot of how subjective viewpoints crystallize into rules that can feel, and sometimes function, like universal truths.

The Illusion of Universal Morality

One of the first targets of deconstruction is the notion of a universally valid morality. Moral realists assert that some actions are intrinsically right or wrong, independent of who judges them. In everyday life, we see this in the confidence with which people say, “X is just wrong, period,” implying a truth as self-evident as the laws of physics. Historically, most people have indeed believed that “moral questions have objectively correct answers”. For example, many would agree that cowardice is bad or heroes deserve respect and treat these claims as “obviously and objectively true”. This mindset underpins everything from religious doctrines of universal sin to Enlightenment theories of natural rights and duties.

However, when we scratch the surface of so-called universal morals, cracks of cultural diversity and disagreement begin to show. What one civilization extols as virtue, another condemns as vice. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus illustrates this with a poignant anecdote: King Darius of Persia observed that Greeks burned their dead while a tribe called the Callatiae ate their dead fathers’ bodies, each culture finding the other’s practice utterly abhorrent. The lesson Herodotus drew was “custom is lord of all”, for people’s beliefs and practices are shaped by custom, and each group assumes its own ways are best. In other words, what feels like an objective moral truth (“Of course, one must honor the dead in our way!”) may actually be a local custom elevated to the status of eternal law. This insight was not lost on ancient thinkers. Sophists like Protagoras declared that “man is the measure of all things,” implying truth (moral truth included) is relative to the human perspective. Even Plato, in recording debates with characters like Thrasymachus, noted the unsettling idea that “justice is nothing but the advantage of the stronger,” suggesting moral rules serve the interests of those in power rather than some higher reality.

The postmodern stance builds on these observations to challenge the very existence of a singular moral reality. Postmodern philosophers are, as Lyotard famously put it, “incredulous toward metanarratives.”

A metanarrative is a grand story or universal framework that claims to explain and legitimize knowledge or values for everyone. Universal morality, the idea that one moral code is objectively valid for all cultures and contexts, is precisely such a metanarrative. Postmodern thought expresses profound skepticism toward it. It questions whether any moral framework can escape the biases of the particular culture or worldview that produced it. Rather than one true morality, there are many moral languages and stories, each contingent on history and social conditions.

This does not mean postmodernism leads to anarchy or the end of moral discussion. Rather, it deconstructs the aura of sanctity around claims of absolute rightness. To deconstruct, in the Derridean sense, is to take apart the constructed binaries and assumptions in a concept, in this case, the binary of Right vs. Wrong, or moral truth vs. moral falsehood. The process reveals that what we often treat as natural or given (like a timeless moral law) is in fact built on layers of interpretation and context. Thus, the illusion of universal morality is exposed: those shining ethical principles said to be written in the stars turn out to be written by us, fallible humans, in the sand of cultural circumstance.

Over a century earlier, Friedrich Nietzsche arrived at a similar conclusion through his genealogical critique of morality. Nietzsche provocatively claimed “there are no moral phenomena, only moral interpretations of phenomena”. This striking statement encapsulates the perspectivist idea that what we call a “moral fact” is always an interpretation from a particular perspective. The world by itself is value-neutral; it is we who paint it with moral colors. For example, imagine observing a simple act like a person taking food from a store. Is it theft (immoral) or justified hunger (moral)? The phenomenon alone, someone taking food, is not self-evidently moral or immoral. It is our interpretation, filtered through our values and context (perhaps “stealing is wrong” versus “feeding the hungry is right”), that labels it one or the other. Nietzsche’s broader project in works like Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morals was to show how moral values (like “good” and “evil”) have histories and serve the psychological or social needs of those who adopt them. In his analysis, concepts of good and evil are not universal constants but arose from the perspectives of different groups, for instance, the oppressed form a morality that makes a virtue of their weakness, calling it “good,” while the powerful have a morality that celebrates strength and calls it “good.” Each is “true” only from a certain viewpoint; there is no view from nowhere.

To make this idea more concrete, consider a simple thought experiment of moral perspective. Two friends, Alice and Ben, witness a third friend make a life choice that might be harmful. Alice believes honesty is the paramount moral rule; she feels she must tell the harsh truth to the friend about the potential harm. Ben, however, prioritizes compassion and the friend’s autonomy; he feels it would be morally wrong to impose an unsolicited judgment that might hurt the friend’s feelings or agency. Alice and Ben thus arrive at opposite moral prescriptions in the same situation, one says confronting the friend is the right thing, the other says it is wrong. Who is objectively correct? From Alice’s perspective, moral duty demands truth-telling; from Ben’s, moral duty forbids it. A moral realist might try to argue that one of them is in fact wrong according to some higher standard. But in a subjectivist light, each is “right” relative to their own framework of values, and there may be no neutral way to adjudicate between the two. The point of this thought experiment is not to trivialize moral dilemmas, but to show how sincerely held moral principles can diverge. Without appealing to a presumed universal law, we are left recognizing that moral judgments ultimately depend on perspective – the subjective lens through which we interpret actions and outcomes.

Subjectivity also operates at the level of entire communities and cultures. Different societies develop different moral outlooks – and each tends to regard its own as natural. An action deemed virtuous in one culture might be scandalous in another. For instance, imagine an anthropologist from a completely foreign society observing our practices: they might be baffled why in some cultures it is immoral for a woman to appear with uncovered hair, while in others this is a non-issue; or why some societies prize filial piety above all, whereas others prioritize individual freedom even if it means disobeying parents. None of these practices carry inherent moral meaning on their own – it is the cultural perspective that imbues them with value. The anthropologist, hopping between cultures, sees that morality is a moving target, defined within cultural narratives. This scenario echoes the real observations of anthropologists and philosophers who note the bewildering diversity of ethical norms around the world. It suggests that moral “truths” function more like local customs that make sense within a form of life, rather than universal laws binding on all humans.

The Social Construction of Moral Values

Zooming out from the individual perspective, postmodern thought emphasizes that our moral frameworks are not just idiosyncratic personal choices, they are deeply social. Morality is a kind of social language, a product of communities in conversation with themselves about how to live together. As such, it is continually constructed and reconstructed through social practices, institutions, and power relations. Postmodernists deny that there are objective, or absolute, moral values; instead, “reality, knowledge, and value are constructed by discourses; hence they can vary with them.” In plainer terms, what a society comes to see as “valuable” or “good” is a result of that society’s ongoing dialogue and contingent history, its literature, laws, religion, science, and everyday interactions. Change the discourse, and the values often change with it.

Consider how drastically moral views have shifted over time within the same culture. In medieval Europe, for example, heresy (holding unorthodox religious beliefs) was seen as a grave moral sin deserving harsh punishment; today, the freedom to believe or not believe is cherished as a core moral principle in Western societies. At one time, charging interest on a loan was morally condemned as “usury”; now an entire global finance system runs on interest, largely unquestioned by our moral conscience. These shifts are not because we discovered some eternal truth that everyone had missed, but because society’s discourse changed through processes like the Enlightenment, secularization, economic development, and social movements, new narratives emerged about religion, personal rights, and economics. The moral values evolved accordingly, constructed through new social understanding.

We can also look cross-culturally for evidence of construction.In Confucian societies, respect for elders is an absolute moral tenet; in certain Western contexts, youth independence is valued and the elderly have less authority. Ancient Sparta historically celebrated martial virtues like honor in battle, while Quaker communities prioritize pacifism and see martial glory as barbaric.These differences do not indicate that one culture found the true morality and the other is mistaken; rather, each culture has built a moral world that aligns with its own history and needs. Morality, in this sense, is akin to a cultural artifact, a crafted thing, not a discovered thing.

Philosopher Richard Rorty captures this idea succinctly when he says, “Morality is not something dictated by external authorities; it is something we construct through social practices.”

We can imagine moral norms as a kind of implicit social contract that communities continually rewrite. There is no abstract authority handing down the rules (or if there is believed to be, that belief itself is a social construction), so people negotiate among themselves – through language, through power struggles, through mutual influence – to decide what will count as virtuous or evil, permissible or forbidden.

This constructive process often happens unconsciously over generations, which is why moral norms feel so natural to those who inherit them. Yet, history and anthropology give us the distance to see these norms as contingent. They could have been otherwise, and indeed for someone else they are otherwise. From a postmodern vantage, moral norms are a kind of collective fiction, albeit a powerful and sometimes necessary fiction. They are more like local customs writ large than edicts from the universe.

One might worry that calling morality a “fiction” or “social construction” undermines its importance. But note, to say something is socially constructed is not to say it is trivial or easily changed. Language itself is socially constructed, but that hardly makes language insignificant or completely malleable at an individual’s whim – it is deeply rooted in social usage. The same goes for moral language: terms like justice, honesty, or harm gain their meaning from how we use them in society, and those meanings can be stable over long periods. What the postmodern approach emphasizes, however, is that we should not mistake this socially engineered stability for an eternal, context-independent truth. Our shared moral vocabulary is always subject to renegotiation when new voices enter the conversation or old power structures shift.

Power, Discourse, and Moral Context

Any discussion of social construction must also reckon with power. Who participates in the construction of morality? Who gets to define the dominant narratives of right and wrong? Postmodern thinkers like Michel Foucault argue that power and knowledge are intertwined and this applies to moral knowledge as well. Moral norms often serve the interests of the powerful, even as they present themselves as universal and benign. Foucault famously noted that “Power is anything that tends to render immobile and untouchable those things that are offered to us as real, as true, as good.” In other words, power operates by taking a certain perspective (often the perspective that benefits those in power) and locking it in as the Reality, the Truth, the Good. Once a moral claim becomes dominant (“untouchable”) in this way, it self-perpetuates: people accept it as just the way things are.

Throughout history, we can observe how power structures shape morality. Consider the rigid class systems or caste systems that existed (and in some places still exist): those at the top of the hierarchy often promulgated moral codes insisting that hierarchy is natural and just. It was moral for everyone to “know their place.” Disobedience, rebellion, or even upward mobility could be painted as moral failings. Why? Because such a moral narrative protected the position of the powerful. Similarly, colonial powers during the Age of Empire carried a narrative that it was their moral duty to “civilize” other peoples, a convenient story that justified conquest and exploitation under the guise of ethical improvement. The colonized, meanwhile, were often portrayed as morally inferior by nature until they adopted the colonizer’s values. Here we see moral universalism used as a tool of domination: one group’s local values were universalized and imposed on others, dismissing any native moral frameworks as irrelevant or wrong. In retrospect, it is clear these claims to universal moral truth were less about truth and more about control.

Nietzsche, in his genealogical approach, also understood morality in terms of power dynamics. His concept of master morality vs. slave morality posited that what the noble or powerful classes in a society find good (e.g., strength, pride, dominance) might be exactly what subordinate classes label as evil; conversely, the traits the powerless find good (e.g., humility, sympathy, patience) are those the powerful scorn as weakness. Each moral outlook serves the interests of the group that holds it. Though “master” and “slave” here are metaphorical to some extent, Nietzsche was pointing to a real historical process: moral values emerge from conflict and negotiation between different social forces. The upshot aligns with a postmodern insight, morality is deeply contingent on context and often encodes power relations. What is touted as “rational, objective morality” in one era might later be unmasked as a rationalization for that era’s power structure.

Importantly, power does not only operate at the grand scale of empires and class struggle; it also operates in everyday discourse. Social norms about gender, sexuality, race, and other identities have frequently been established by those in dominant positions defining what is “normal” and “moral.” For instance, if a particular religious or political ideology dominates a community, it will shape the moral discourse to reflect its values (condemning certain behaviors, elevating others) in a way that can exclude or stigmatize minority viewpoints. The moral code thus becomes an enforcement mechanism: straying from it invites sanction, while adhering to it gains approval. In this light, one might say moral judgments are instruments of social regulation, not mirrors of some independent moral reality.

While Foucault’s analysis illuminates how power stabilizes moral norms, an even earlier commentator on power was Niccolò Machiavelli. Writing in the early 16th century, Machiavelli advised rulers to treat moral precepts not as absolute prohibitions, but as flexible instruments for retaining control. His approach dispensed with universal moral codes in favor of pragmatic tactics, whatever serves the ruler’s ends is effectively “right.” This unabashed strategic bent resonates with the idea that morality is often shaped, or even fabricated, by those in power. From a postmodern standpoint, Machiavelli’s candid counsel underscores how ethical labels, whether “virtuous” or “deceitful”, emerge from social consensus and can be used to achieve desired outcomes. In other words, his viewpoint neatly illustrates omnimoral subjectivism: moral principles function as practical tools rather than fixed truths, reconfigured at will to fit the demands of the moment.

Foucault’s insight that power makes certain ideas “immobile” means that once a moral norm is established by power, it resists critique, questioning it might itself be deemed immoral or taboo. For example, questioning the moral code of a religious community from within that community can result in one being labeled heretical or evil, a move that protects the code from change. However, postmodern critique aims to unmask this dynamic. By recognizing that power hides behind claims of moral truth, we can start to loosen the grip of seemingly immutable norms. This does not mean that all norms are only about power (many moral norms do serve genuine social well-being), but it means even well-intended norms require scrutiny of whose perspective they serve and whom they might silence.

Beyond Binary: Morality Without Absolute Opposites

Conventional morality often relies on neat binary oppositions, good/evil, right/wrong, innocence/guilt. These binaries imply clarity: an action or person firmly belongs in one category or the other. A postmodern lens, influenced by deconstructive philosophy, questions such either/or dichotomies. Real life, and real moral experience, is seldom so black-and-white. When we examine how moral judgments are formed, we frequently find ambiguity, gray zones, and contradictions that resist simple classification.

Deconstruction, as developed by Jacques Derrida, suggests that binary oppositions are inherently unstable. Each term in the pair derives meaning from its opposite, good has meaning only in contrast to bad, for instance. This interdependence means the boundary between the two is porous, not absolute. Furthermore, one side of a binary is usually privileged (good over bad, right over wrong), creating a hierarchy. Postmodern ethics invites us to turn a critical eye to these hierarchies and ask: who benefits from drawing the line here and not elsewhere? What complexities are being flattened by the insistence on either/or?

For example, consider the moral binary of truth vs. lying. In a simplistic moral narrative, truth-telling is good and lying is bad, always. But there are times when these categories blur, a “truth” can cause harm, a “lie” can show compassion. Is a compassionate lie that does no harm bad simply because it’s a lie? A rigid moral binary would force a yes or no answer, yet our moral intuition struggles here. It senses that the context, the motive, the outcome, and the relational dynamics, all matter in judging the act. This is an instance of moral continuum rather than binary: truth and falsehood exist on a spectrum with various shades (white lies, half-truths, polite fictions) that resist labeling as purely right or wrong. A postmodern approach leans into these gray areas, seeing them not as bugs of moral reasoning but as features of it. Morality is a fluid interplay, not a static binary, an interplay of competing values and interpretations that cannot be cleanly resolved into absolute categories.

None of this is to say that we cannot make moral judgments or that all is moral chaos. Human societies will always create norms and rules, some behaviors will be endorsed and others condemned. The key point is recognizing the fluidity and contestability of those norms. A consequence of this recognition is increased moral humility: if we know our binaries and judgments are not the One True Morality but one set of interpretations, perhaps we become less quick to condemn others outright. We might instead ask why they see things differently, what values lead them there, and whether our own certainty is as justified as we assume. In a way, abandoning strict binaries opens a door to dialogue and understanding – a hallmark of the postmodern ethos is to value conversation over dogma.

Subjective Relativism: Clarifying the Critique

Building on the earlier discussion of postmodern skepticism toward universal morality, it is worth focusing on one of the most frequently misunderstood positions: relativism. Properly speaking, relativism asserts that moral judgments and values depend on cultural, social, or individual standpoints. However, critics often reduce this view to the sweeping claim that all moral or truthful assertions must be treated as equally valid. Under this misreading, a culture’s condemnation of theft would be placed on par with another’s celebration of theft, as though each view deserved identical weight just because it exists.

Such an assumption is not intrinsic to relativism itself. Relativism, in its more precise form, says only that truth claims emerge from particular subjects or contexts, not that every claim is correct. In fact, as soon as we reject someone’s moral or factual claim “I do not accept your position on theft,” for instance we are paradoxically demonstrating how relativism operates: my critique arises from my perspective, shaped by the moral norms of a particular time and culture. The notion that relativism “makes all perspectives equally valid” is therefore a misunderstanding: recognizing the context-bound nature of truths does not oblige us to endorse them without question.

When viewed through a postmodern lens, we see how the “all claims are equally valid” critique stems from a deeper discomfort with the absence of a universal grounding. Yet, relativism simply underscores that shared norms are negotiated and sometimes contested rather than handed down from an ultimate source. We are always free to reject, condemn, or modify someone’s moral stance. Doing so does not break relativism; it exemplifies it.

To appreciate the extremes of subjective relativism, consider how moral truths might unfold in total isolation. Imagine a person fully immersed in a simulation, cut off from contact with other human beings and interacting only with sophisticated AI. In this solitary bubble, the AI could reshape the environment to conform precisely to the individual’s beliefs, so that every assertion, no matter how bizarre, becomes “true” for that person. If they believe the world is flat, the simulation would bend to make it so.

In this scenario, moral or factual claims face no external challenges. The self-referential reality within the simulation removes competing truths. While this might look like “all claims are equally valid,” a more accurate reading is that one person’s viewpoint reigns unopposed because there are no other subjects or contexts to press back. If we amplify that isolation technologically, the subject’s moral universe can become entirely self-sustaining.

Even under normal circumstances, each of us begins as an isolated consciousness. We only discover other moral systems and refine or abandon our own when we clash or converge with outside perspectives. The radical isolation of a simulation simply extends this logic to its furthest limit: if no one else can contest our worldview, our private set of truths achieves unchallenged status. It does not imply that any claim is universally “valid,” only that validity becomes meaningless in the absence of other viewpoints.

Relativism thus does not require that we refrain from judging or critiquing moral claims. Rather, it demands we acknowledge that judgments themselves come from particular vantage points, shaped by history, social forces, and personal psychology. Far from championing moral equivalency, a robust relativism highlights the contingency of all claims, which includes our right to reject those we find harmful, incoherent, or oppressive. In this sense, we remain accountable to the immediate consequences of moral decisions in our shared world.

Seen this way, relativism does uphold diversity of perspectives but does not say we must accept every perspective as legitimate. The real question becomes which perspectives resonate or clash with others to the extent that they gain broader social traction. When enough subjects agree on a moral principle, whether through persuasion, negotiation, or power, the principle becomes “dominant.” Its dominance, however, is always open to challenge, revision, or outright rejection by future voices and contexts.

Questioning Moral Realism and Ethical Objectivity

By now, a picture has emerged of morality as a contingent, constructed, and contested domain. Let us crystallize how this challenges the claims of moral realism and ethical objectivity. Moral realism, in philosophical terms, is the position that there are objective moral facts or truths, that statements like “murder is wrong” or “charity is good” are true or false independent of human opinion, much as “the Earth orbits the Sun” is true regardless of belief. The preceding discussions and scenarios cast doubt on this position from multiple angles:

Disagreement and Diversity: If moral facts were as clear-cut as realists suggest, why do we see such persistent, deep moral disagreements across cultures and eras? The moral realist might counter that some people or cultures just get it wrong about the moral facts (just as some cultures historically got the shape of the Earth wrong). But unlike factual disagreements which can be resolved by evidence, moral disagreements often persist even when all parties are fully informed and rational. This suggests that it’s not just ignorance of an objective truth causing disagreement – rather, people are working from different foundational values. The postmodern perspective would say those values are products of different narratives and power structures, not misperceptions of a singular moral reality.

Underdetermination by Nature: The natural world does not straightforwardly tell us how to behave. From a scientific perspective, humans are animals with evolutionary drives, but no observer of nature alone can deduce a moral law (a point made famously by David Hume’s is/ought problem). Realists often posit a realm of moral truths beyond the empirical. Postmodern skeptics find this unconvincing; it appears that whenever we claim to have found a moral law in nature or reason, we are really imposing a value-laden interpretation. What we consider “natural” is itself often socially constructed. For example, appeals to what is “naturally right” historically have justified everything from rigid gender roles to free-market competition, yet these appeals often reflect the biases of their time. By highlighting the contingency in those appeals, we see that nature underdetermines morality – meaning nature (or pure reason) doesn’t force one moral conclusion; humans must choose and construct one.

Genealogy and Self-Reflection: Nietzsche’s genealogical critique and similar analyses by others (like anthropologist Ruth Benedict or philosopher Michel Foucault) show that many moral values can be traced to non-moral origins: fear, historical accident, economic interest, power grabs, religious narratives, and so on. When we become aware of the genealogy of our morals, it undercuts their claim to objectivity. If what I deemed a universal moral truth is revealed to have, say, originated in the propaganda of an ancient ruling class or the edicts of a particular religion, I might start seeing it as “true for them then” but not binding for all. Moral realist theories, whether based on divine command, rational intuition, or utilitarian calculation, often assume a kind of ** ahistorical viewpoint**. Postmodern thought injects history and context back into the equation, which makes moral realism much harder to sustain. Every purported eternal truth comes with a history that can be scrutinized and deconstructed.

The Failure of Foundationalism: Ethicists who seek an objective basis for morality often try to ground it in something solid: God’s will, human nature, rational consistency, etc. Postmodern skepticism, influenced by what philosophers call anti-foundationalism, doubts that any such foundation can escape being just another narrative. If one says, “Objective morality comes from God,” that presupposes a particular theological narrative which is not universally shared (and is itself a matter of faith, not proof). If one says, “It comes from rational principles,” we find that different thinkers’ rational principles lead to different moral systems (Kantian duty, Mill’s utilitarian happiness calculus, etc.), so which rationality is the truth? Each foundational claim seems to either exclude some perspectives arbitrarily or smuggle in values that are not themselves justified by pure objectivity. The postmodern view is comfortable with the idea that there is no final foundation, that moral reasoning is a circular, conversational process rather than a pyramid resting on a single rock-solid premise.

At this point, one might ask: if morality isn’t objective, why do we all often feel so strongly about it? Is it all just an illusion or a power game? Postmodern thinkers wouldn’t deny the felt reality of moral experience, indeed, they often emphasize it. We feel our morals deeply because we are socialized into a particular form of life that gives them significance; we develop emotional attachments to certain values (like justice or loyalty) that become part of our identity. These feelings are real, but their objects (the moral rules themselves) remain contingent. An analogy can be made with language again: I feel the meaning of my words and thoughts, yet the language I use is one of many possible languages. Someone speaking another language feels their meanings just as strongly. Likewise, a person in another moral culture feels the weight of their moral rules just as we feel ours. There is no contradiction here once we accept a pluralism of moral worlds.

To say “there are no absolute morals” is not the same as saying “there is no morality.” It means there is no morality from a God's-eye view, but there are many moralities from the human view. Each functions in its context, and can be evaluated internally (we can ask if a society’s practice is consistent with its own values or if an individual is living up to their professed principles, etc.). We can also critique each other’s morals externally, but those critiques too will come from another set of values. Postmodern ethics tends to replace the quest for universally correct morals with a quest for mutual understanding between different moral outlooks, and perhaps an exploration of new possibilities not bound by any single tradition.

Rejecting Objectivity: The Epistemic Foundation of Omnimoral Subjectivism

A thorough critique of universal morality must also reckon with the tension between a priori truths and the role of the subject who asserts them. In traditional philosophy, an a priori claim like “all bachelors are unmarried” or “7 + 5 = 12” is said to be true independently of experience. Many moral theories likewise strive to position moral statements as necessarily true, valid regardless of personal bias or cultural variance. However, closer inspection reveals that even a priori truth claims depend on a subject to formulate, endorse, and interpret them.

The hallmark of an a priori claim is that it appears logically undeniable. For instance, if morality were a priori, it would follow that “killing is wrong” remains true in all contexts, no matter who observes it or under what conditions. But observe that such a statement still requires a conscious subject to conceive it, defend it, and apply it to concrete situations. A solitary, mind-independent realm of moral truth does not spontaneously announce “killing is wrong”; rather, we, as subjects, do the announcing. Any moral principle, be it about harming others, telling the truth, or honoring one’s commitments, only gains meaning when a subject infuses it with interpretive content.

This point extends to all a priori-seeming knowledge: geometric theorems, mathematical truths, logical tautologies. While these might be valid in a strictly formal sense, their real-world significance depends on how individuals grasp and deploy them. A triangle’s three-sidedness might be analytically certain, but the importance we give that certainty arises from human interpretation and cultural consensus (for example, in how we teach geometry or structure architecture). In short, the “universal” status of a priori statements does not negate their reliance on subjects who determine what is worth calling universal in the first place.

All moral declarations, whether they invoke God, reason, social contracts, or intuitive duty, aspire to truth. To say “This act is morally wrong” is to make a claim about the world that we want others to accept as valid or correct. Yet the moment we label it a truth claim, we face the same dilemma as with any other proposition: Who is speaking it, how is it warranted, and why does it bind anyone else? From a subjectivist vantage, moral judgments do not simply float outside time and space; they emerge when a moral agent constructs meaning and says, “I find this to be right (or wrong), and I regard that stance as true.”

This realization prompts a more general conclusion about objectivity. If we cannot locate a single, mind-independent source for moral law, and if every statement of moral “fact” requires a subject to articulate it, then what does objectivity amount to, beyond robust intersubjective agreement?

Accepting the subject-dependent character of moral claims undermines the classic vision of objectivity as “truth outside perspective.” In many fields, science, mathematics, everyday language, what we call “objective” is largely a broad consensus that holds up across varied contexts. There is nothing inherently wrong with consensus (it helps us coordinate, reason together, and transmit knowledge), but we should recognize how it can feel deceptively absolute. Once enough people internalize a particular moral principle, it acquires the appearance of a universal truth. Historical shifts in consensus, however, reveal how easily purported moral absolutes can fall away when new voices or arguments enter the conversation.

Hence, what is customarily dressed up as “objective morality” may be a social agreement so widespread that it passes for fact. Should that agreement change, the moral “fact” does, too. A subjectivist approach does not deny the force of shared morality, indeed, it highlights how communities shape and reinforce norms, but it does deny that any moral standard can be verified as mind-independently true.

Since every truth claim (including moral assessments) must be made by a subject, and since even a priori-sounding moral principles rely on an agent’s act of interpretation, the stage is set for omnimoral subjectivism. In essence:

No External Anchor: If objectivity is just consensus, rather than a transcendent fact, then there is no external anchor for morality. We cannot appeal to an ultimate yardstick that trumps all subjective perspectives.

Centrality of the Subject: Because all moral assessments, from “Murder is wrong” to “Generosity is virtuous,” arise from a subject, it follows that moral rules are as flexible as the interpretive communities that form them.

The Nature of “A Priori”: Even moral claims that feel self-evidently true become meaningful only when a subject frames them that way. Saying “this is obviously wrong” actually means “given my internal framework and the moral lens of my culture, I see no logical way around condemning it.” That’s powerful, but still subject-based.

Contingent Norms, Convincing Force: Recognizing these claims as subject-based does not cheapen moral discourse. Moral convictions can still exert tremendous force, people have died (and killed) for them. But the recognition that moral truth depends on interpretive acts can promote humility in how we defend or spread our views.

In short, what some philosophies hail as the a priori grounding of morality comes down to how strongly certain moral claims are woven into our conceptual scheme. From the vantage point of omnimoral subjectivism, that conceptual scheme is never “above” subjectivity; it is built from within, by individual perspectives that align or conflict.

Omnimoral Subjectivism

Omnimoral subjectivism holds that any act can acquire moral significance once someone, anywhere, imposes a moral lens upon it. The “omnimoral” aspect emphasizes how morality can permeate every choice when observers, whether they be the actor themself or outside assessors, interpret it as either right or wrong. At the same time, the “subjectivism” component underscores that no single vantage point or set of moral rules has universal authority; judgments ultimately rest on personal or cultural viewpoints. By positioning all moral evaluations as context-bound and individually derived, this approach avoids insisting on any absolute moral codes, however it does not slide into moral chaos, precisely because moral significance can emerge whenever groups or individuals decide it matters.

Having explored the ways postmodern skepticism complicates any fixed moral order, we might wonder whether this fluidity condemns us to a moral free-fall. Is there an approach that formalizes moral behavior without resorting to rigid universalism? Contractarian theories attempt to answer this question by grounding morality in rational consensus among individuals. In these frameworks, moral norms emerge when agents realize that rules promoting cooperation and fairness ultimately serve everyone’s long-term interests.

David Gauthier’s Morals by Agreement (1986) develops such a contractarian view, rooted in rational choice theory. He posits that moral principles do not arise from divine command, innate moral facts, or categorical imperatives but from mutual agreements among rational agents who seek to maximize their self-interest. Gauthier refines Hobbesian contract theory through the principle of constrained maximization, which explains why rational individuals, looking beyond immediate gain, willingly accept moral constraints that benefit them in the long run. Although his account is a rigorous model of morality as strategic cooperation, it rests on quasi-objective rational structures, assuming that, under suitable conditions, rational actors will converge on shared moral rules. From a postmodern vantage, this limitation points to an underlying presupposition: moral order is the product of reasoned consensus rather than the kaleidoscope of subjective standpoints and changing power relations. My position diverges precisely on this point. Instead of seeing morality as an outcome of stable agreements among rational actors, I contend that moral judgments materialize through the ceaseless interplay of subjective valuations, narrative frames, and contextual incentives. Morality is less a contract forged under static conditions and more a dynamic game in which both the rules and the payoffs, and even the sense of what “the game” is, keep shifting. Where Gauthier locates morality in a rational accord, I locate it in ongoing social construction, forever contested and reconfigured.

How, then, do we decide what to do when no permanent, universal code guides us? On the surface, each choice, be it crossing the street or selecting a meal, might seem purely practical: we want to survive, thrive, or feel content. However, when we invoke morality, we imply a stronger claim: that some course of action is not just personally beneficial, but right, binding on all who share relevant perspectives or values. A postmodern, subjectivist view suggests that moral judgment does not exist in a vacuum. Rather, it is activated within a dense web of interactions, shaped by social context, subjective desire, and shifting power balances.

Therefore, morality does not pre-exist human interpretation as a stable, external realm. Instead, it manifests whenever individuals or groups decide that a particular choice bears moral weight. By highlighting this fluid and context-bound nature of ethics, omnimoral subjectivism reveals how personal commitments, cultural narratives, and power relations all shape whether an act is deemed right or wrong. Furthermore, a game-theoretic lens clarifies the shifting incentives behind these judgments, illuminating how moral significance can attach to practically any decision. Rather than functioning as a rigid universal code, ethics becomes a special category of assessment that arises the moment we, or our assessors, cast an action in moral terms. In the sections that follow, I describe how this framework reframes our understanding of right and wrong, showing why moral authority cannot be secured by appealing to any single, overarching standard..

The Game-Theoretic Turn: Actions, Payoffs, and Moral Assessments

From a distance, game theory might appear to be a purely mathematical framework tailored to economics or political science. Yet its core ideas, actors making choices based on incentives, information, and possible outcomes, apply broadly to human decision-making. Classic examples such as the Prisoner’s Dilemma illustrate how individual self-interest sometimes leads to collectively worse results, but the real value of game theory here is broader: it gives us a language for describing choices, strategies, and payoffs, all of which can be reinterpreted in moral terms when observers or participants overlay a moral lens on the outcomes.

Actors: Individuals (or groups) making choices, each guided by personal or cultural values, motivations, and constraints.

Strategies: Possible courses of action (e.g., tell the truth, remain silent, cooperate, defect), each linked to certain outcomes.

Payoffs: The perceived costs or benefits to an actor, these may be material, social, emotional, spiritual, or a mix of all four.

Observer: A witness who does not issue a moral judgment.

Assessor: An observer who actively pronounces an act morally right or wrong. An assessor is therefore always an observer, but an observer is not necessarily an assessor.

An everyday strategic decision, “Should I cross here or at the light?”, becomes a moral decision once someone interprets it through the lens of right and wrong. In this sense, morality rests not in the action itself but in the interplay of subjective payoffs across multiple perspectives. It hinges on an assessor, and the actors themself (who are also assessors), who insists that a particular choice bears moral weight. Ethics thus emerges whenever we attach a moral dimension to our strategic decisions, turning them into something more than mere moves in a game of pure self-interest or convenience.

In many daily transactions, like choosing a sandwich for lunch, no moral dimension arises. It is a pragmatic decision, influenced by hunger, taste, cost, or convenience. But if an assessor believes that consuming meat is inherently wrong, or that bread is sacrelegious (the reason is only relevant in so much that the assessor perceives wrongdoing) that same sandwich purchase suddenly becomes “morally charged.” A moral assessor has entered the game, imposing a moral dimension on what the eater might otherwise see as a trivial choice. Thus, an ordinary choice becomes an ethical choice when at least one subject sees it as having moral weight.

We might call this the “moral upgrade”: the action itself (A) plus the assessor’s (including the actor’s own) moral lens (L) yields a moral assessment (M):

Here, L is the lens, the moral schema or framework that invests an act with significance, turning it into a moral question. Without L, the act remains ethically neutral, like a move in a purely technical game. With L, the act is no longer neutral; it is subject to moral scrutiny and potential social or personal repercussions. In this scenario, we have two actor, two lenses and two moral outcomes. A third actor, lens and moral outcome could be you, the reader, making an assessment of the decision as either moral or not.

Moreover, the very act of declaring a moral judgment can trigger what we might call an “assessor awakening.” An observer may exist in a state of ethical neutrality, unmindful of any moral dimension to the action, until another party’s assessment brings it to the forefront. At that moment, the observer, newly aware of the moral framing, often feels compelled to weigh in: acceptance, rejection, or an alternative moral stance. This shift underscores how a single labeling of an act as moral (or immoral) can reverberate through additional viewpoints, turning previously indifferent onlookers into active moral assessors in their own right.

Imagine a municipal recycling program. For many, tossing a plastic bottle into the trash can is no more a moral decision than picking which pair of socks to wear, unless an assessor or the individual themself (also an assessor) invests that act with moral significance (“not recycling is wrong because it harms the planet and future generations”). As soon as that moral lens appears, the actor’s payoff changes: they risk guilt for not recycling, or social disapproval from environmentally conscious friends. Conversely, if the local culture sees no moral dimension to recycling, the game remains a purely pragmatic one: “Which bin is closer?” or “Do I get a recycling deposit refund?”.

This everyday scenario highlights how any act could, in theory, become moral or remain morally neutral, depending on whether it draws the attention of a moral assessor. Ethics thus diverges from a standard “rational choice” by adding layers of emotional, social, or symbolic payoffs (or punishments) that revolve around moral condemnation or praise.

In fact, these dynamics are not abstract possibilities; they reflect how moral judgments already function in our day-to-day lives, albeit often unnoticed or dressed up in the language of universal standards.

Ethics in a Postmodern, Subjectivist Light

Drawing on postmodern skepticism toward grand narratives, we can see how game theory operates within a variety of moral frameworks. Each actor’s choice is embedded in social contexts that determine which payoffs matter and which are dismissed. Moreover, as soon as an action is judged morally by at least one participant or assessor, the entire game changes.

The Fluidity of Payoffs

Postmodern thought emphasizes that moral values and priorities are far from universal. One individual might care deeply about financial gain, another might single-mindedly seek personal happiness, and yet another might prioritize loyalty to family or religious devotion. All of these payoffs can be shaped by history, culture, and, crucially, emotional drivers. As philosopher Jesse Prinz points out, moral judgments often stem from affective responses: we tend to call actions “right” or “wrong” based on how they resonate with (or disrupt) our emotional comfort. Put differently, not infringing upon moral rules can be seen as a way of avoiding the suffering, guilt, shame, anxiety, social disapproval, that might follow a “wrong” act.

Because emotions vary widely among people, moral controversies often hinge on actors holding different payoffs. One person could see “telling the truth” as a sacred duty, refusing to lie even if it hurts someone’s feelings, while another might weigh truth-telling against the harm they believe it might inflict. Both actors are “rational” from a game-theoretic standpoint: each maximizes what they perceive to be the best outcome. Yet their respective payoffs differ because each draws on a distinct blend of emotional values and cultural norms. Consequently, a single event, such as choosing whether or not to deliver a painful truth, can generate opposing moral judgments.

Even trivial incidents reveal this divergence. Imagine Anna and Ben waiting in a doctor’s office when someone next to them sneezes:

Anna thinks it is morally right to say “Bless you,” reflecting her cultural upbringing where offering vocal sympathy is a sign of kindness. The idea of staying silent makes her uncomfortable and seems impolite.

Ben believes that calling attention to someone’s sneeze is intrusive, risking the embarrassment of the sneezer. From his perspective, politeness means offering privacy rather than public acknowledgment.

Each is acting in accordance with emotional comfort, Anna’s desire to appear caring vs. Ben’s wish to avoid causing discomfort. Their divergent payoffs, shaped by personal feelings as well as cultural narratives, lead to differing moral assessments of the same act.

This fluidity underscores why postmodern relativism resists the notion of a single, fixed moral standard. People weigh emotional and social costs in myriad ways; what one person regards as a moral imperative may seem wholly optional, or even counterproductive, to another. Thus, moral reasoning becomes a continuous interplay of emotional states, subjective priorities, and cultural framing, rather than a universally applicable calculus.

Distinguishing Ethics from Everyday Decisions

From a subjectivist vantage, not all actions automatically carry moral weight. A key difference between everyday choices and ethical decisions lies in how assessor perceive an action’s outcome. If an actor does A and the result is B, the moral significance of A hinges on several factors: (1) how many people are aware of B, (2) who those people are, since a single influential observer may have as much impact as a large group, and (3) whether B resonates strongly with observers’ values.

If only a few people notice the outcome and regard it as trivial, the act tends to remain ethically neutral. Conversely, if even one assessor with authority or credibility deems B significant, positively or negatively, then an otherwise mundane act can be charged with moral meaning. The actor, in turn, may internalize guilt, pride, or obligation based on that assessment.

In this sense, moral weight arises from the interplay between the outcome’s visibility and the assessor’s influence. The more recognized or controversial B becomes, the more likely it is that assessors, individually or collectively, will treat A as morally relevant. By contrast, a minor or unnoticed outcome might remain an isolated event that never rises to the level of moral scrutiny.

We can model moral weight as a function of three elements: (1) the act (A), (2) its outcome (B), and (3) the assessor set (O). Each assessor oᵢ in O evaluates B with some degree of influence (wᵢ) and moral perception (pᵢ).

Let M(A,B,O) represent the total moral weight:

wᵢ: An assessor’s influence factor (e.g., authority, credibility).

pᵢ(B): The assessor’s perception of B’s moral significance (positive or negative).

The sum of all observers’ weighted perceptions yields M, the overall moral weight.

If M(A, B, O) surpasses some threshold T, reflecting the level at which a society or individual considers B morally notable, then A is treated as a moral decision rather than a mundane one. Below that threshold, A remains ethically neutral.

Power, Payoff, and the Dynamic Construction of Moral Norms

What postmodern theory helps us see, beyond the game-theoretic structure of choices, is the role of power in shaping which payoffs get recognized as valid and which moral frames prevail. Not only do individuals subjectively value different outcomes, but entire societies tilt the scales by punishing or rewarding actions. If enough individuals or sufficiently powerful institutions label a certain behavior “immoral,” that label can carry real consequences in economic opportunity, social status, and even personal safety. Thus, the moral lens is not just a gentle overlay, it can become a potent force reconfiguring the game.

Incentivizing Moral Alignment

Law offers one of the clearest examples of how a society formalizes its moral stance, setting a standard that extends beyond any single individual’s perspective. From a postmodern point of view, this standard is not automatically universal: it stems from collective consensus (or the will of those in power), yet it can profoundly affect individual decision-making by altering the strategic “payoff matrix.”

Consider a law banning theft. Before legal restrictions, an actor might view taking someone else’s property as a quick, low-risk gain. Once the law is in place, however, the associated penalty, potential arrest, fines, or imprisonment, shifts the cost-benefit calculation in game-theoretic terms. The actor must now weigh their desire for immediate profit against the threat of legal sanctions, plus any added social stigma attached to criminal behavior. In effect, law changes the potential payoffs, incentivizing moral alignment with the codified standard.

Yet the presence of a legal rule does not guarantee unanimous compliance or universal moral agreement. Some individuals may resist or disregard the law if they believe their personal, cultural, or emotional payoffs outweigh the risks. For instance, someone could justify theft out of perceived necessity (to feed a starving family), while another might simply judge the law as unfair or illegitimate. From a postmodern vantage, this highlights that law, though it aspires to collective endorsement, remains a social construct, potent enough to guide or punish behavior, but neither transcendent nor objectively “true” in a universal sense.

Nonetheless, the law’s power comes precisely from its formal authority: it is enforced by institutions backed by societal consensus or coercion, making it a tangible factor in most moral calculations. While individuals may or may not factor in the law when deciding right from wrong, the risk of penalties often pushes them to conform to officially sanctioned norms. Thus, when we treat moral judgments as moves in a dynamic game, law becomes a key variable shaping the decisions of rational agents who adapt to the realities of enforcement. By setting an external standard, society effectively recalibrates personal cost-benefit equations, creating a structured incentive for moral alignment, even as the ultimate decision to obey remains subject to each actor’s subjective valuations.

Likewise, social groups of various kinds, from local clubs to expansive religious communities, play a similar role in incentivizing (or disincentivizing) moral behavior. Although they lack the formal authority of a legal system, these groups establish their own codes and expectations, often backed by the threat of expulsion or censure. For instance, a tight-knit religious community might collectively punish an individual who flouts shared norms by distancing themselves from that person or revoking certain privileges. The fear of losing belonging, reputation, or access to communal resources recalibrates an individual’s payoff matrix in much the same way legal penalties do. Viewed through a postmodern lens, these group-generated standards are no more absolute than statutory law, yet they can be remarkably effective in governing behavior. By defining “acceptable” conduct and enforcing it through social sanctions, groups erect an external standard that shapes moral choices, even if each actor remains ultimately free to weigh personal values against the potential costs of noncompliance.

Strategic Adjustments and Moral Fluidity

A subject’s moral stance can evolve when new payoffs appear, whether through changing social norms, newly revealed information, or shifts in personal priorities. If an action once deemed morally inconsequential is suddenly condemned by influential voices, be they laws, communities, or respected individuals, a person may “adjust” their behavior to avoid punishment, shame, or exclusion. From the outside, this can look like a newfound moral conviction, but from a postmodern standpoint, it also reflects a recalibration of strategic incentives. Social rewards or penalties change, prompting the actor to modify what they consider “right” or “wrong” without necessarily discovering a universal moral truth.

Yet sometimes an individual may act inconsistently or even hypocritically, performing behavior in one situation they would condemn in another. For instance, consider someone who publicly preaches financial honesty yet secretly engages in tax evasion. In purely game-theoretic terms, if the person believes they can avoid detection, and thus avoid the negative payoffs associated with social or legal condemnation, they may perceive a higher net benefit from cheating. By contrast, in a scenario where exposure is more likely, the same act might appear too risky or “immoral.” The shifting variable is not the nature of the act (cheating vs. not cheating), but rather how much the actor fears sanction. Consequently, the person’s moral judgment changes even if the act itself does not.

A further complication arises when two identical acts meet contrasting responses in near-identical circumstances. Suppose an office worker makes an offhand remark once on a busy Monday morning, nobody notices or cares, so they feel no moral repercussions. A week later, they make the same remark on another Monday, but this time a colleague takes offense or a supervisor happens to overhear. Suddenly, the worker faces condemnation, leading to a much different payoff equation. While nothing about the remark itself has inherently changed, its moral gravity shifts entirely because the social environment reacts differently. Put simply, whether the actor is impacted by an assessment hinges on who judges the action and how.

These scenarios illustrate the core postmodern claim that moral “truth” resides not in the act alone, but in the evolving interplay of observers, contexts, and incentives. A person’s behavior may flip from being regarded as permissible to transgressive solely due to a shift in which eyes are watching or how severely the group reacts. Morality thus remains fluid: actors continuously gauge the social costs or benefits associated with a choice, and they adapt accordingly, even if that adaptation appears contradictory or hypocritical. This mercurial quality does not necessarily indicate moral depravity or insincerity, it reflects that what truly matters, in practice, is how an act is judged and by whom, rather than any immutable moral property of the act itself.

Any Reason Can Become a Moral Reason

The logic of moral assessments does not rely solely on pragmatic considerations like harm or benefit. In principle, any motivation, no matter how idiosyncratic, can trigger the moral apparatus. Imagine a man who feels intense guilt after chewing green bubblegum because green reminds him of grass, which evokes painful memories of condemnation because grass grows from the ground. Overcome with emotion, he deems his gum-chewing immoral. If this man is the only assessor, the moral dimension exists purely in his personal frame. Whether others see the act as absurd or irrelevant is beside the point; from his vantage, it carries a negative payoff.

This peculiar example highlights a key insight: the reason behind calling something “right” or “wrong” need not be objectively compelling or shared by many. If one subject interprets the action as moral or immoral, the moral game begins, albeit in a tiny, self-contained sphere, but a meaningful one for the assessor. The larger social community may dismiss his rationale, in which case his sense of immorality remains private and maybe short-lived. However, if the same community rallies around this notion, perhaps they share his aversion to green gum, then the act acquires a heavier moral weight, reinforced by collective condemnation.

Thus, from a game-theoretic perspective, any reason can launch a moral assessment, but that reason only matters insofar as it influences the players’ choices and payoffs.Even an instinctual behavior like scratching an itch can become the target of moral scrutiny. Though it may arise as an immediate, reflex-like decision, a moral lens can easily be imposed. Perhaps a single assessor regards scratching in public as indecent or offensive, labeling it a violation of etiquette or respect. In that case, the reflexive act suddenly bears moral significance, regardless of whether any “reason” was involved. In the gum-chewing case, the man’s intense guilt is his own payoff (negative emotional impact), and others’ responses multiply or diminish that guilt. This dynamic affirms how deeply subjective morality can be: while you or I might see no ethical dimension in gum color, for him it becomes a significant transgression. Morality here does not follow a universal standard; it arises whenever someone, for any reason, decides to treat an act as moral or immoral.

Applying a Game Theoretic Approach

Up to this point, we have seen that routine actions remain ethically neutral until at least one observer, be it the actor or someone else, invests them with moral significance. Moreover, social power and authority can amplify or suppress these assessments, radically changing how the actor perceives the ‘costs’ and ‘benefits’ of doing something. In other words, morality is not a property inherent in an action itself; rather, it emerges from the interplay of subjective viewpoints, social norms, and the power to reward or punish. To illustrate how a seemingly mundane act can become morally charged once it is observed or socially contextualized, consider the following scenario of food waste. This example demonstrates how moral lenses, subjective interpretations, and rational incentives intersect to transform an everyday decision into a moral dilemma.

Situation

Actor X finishes a meal at home and has leftover food.

Option A: Discard the leftovers in the trash.

Option B: Store the leftovers for future consumption.

Option C: Donate the leftovers to a local shelter (or share them with a neighbor in need).

Assessor Y observes X’s decision. Depending on Y’s perspective (environmentalist, humanitarian, indifferent, etc.), Y may invest moral significance in the act:

If Y cares deeply about food waste, discarding leftovers might be deemed “immoral.”

If Y sees no problem with throwing food away, the same act might remain morally neutral.

Rational-Choice Outline

Below is a simplified payoff matrix from X’s point of view. We’ll incorporate possible social or internal consequences, guilt, shame, praise, etc., once Y’s moral lens comes into play.

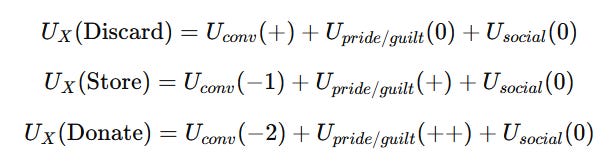

Actor’s Utility Components

Uconv: Convenience or effort cost. (Discarding is easy, storing or donating costs time/effort.)

Upride/guilt: Internal emotional payoff. (Varies if X personally feels discarding is wasteful or not.)

Usocial: Social feedback payoff. (How Y reacts—praise, condemnation, or indifference—affects X’s social or reputational standing.)

Assessor’s Moral Lens

LY: The lens that Assessor Y applies. For instance, Y might weigh environmental harm more heavily, or might not see leftover waste as a moral issue at all.

Action Set for X:

Discard (D): Quick and easy, but may incur condemnation from Y if Y invests moral significance.

Store (S): More effort now, but could reduce waste and condemnation.

Donate (O): Greatest effort, potentially highest moral approval—if Y values altruism.

Payoffs

Let’s propose a simple payoff structure for X, before considering Y’s moral condemnation or praise:

We rank “convenience” as highest (easy) for discarding, moderate for storing, and lowest for donating.

If X has no internal guilt, discarding might initially seem best.

If X or Y invests moral significance, pride/guilt or social payoffs become critical.

Incorporating Condemnation or Praise

If Y strongly condemns waste, discarding yields a negative social payoff −C, while storing or donating yields no penalty (or even a positive payoff +P if Y praises X for saving or sharing food).

If Y sees leftover waste as trivial, then −C or +P is zero. Thus, morality enters only if Y invests moral weight.

Hence, X’s final utilities become:

Whether discarding is “immoral” depends entirely on Y’s lens and how that lens influences X’s perceived payoffs.

Logical Formalism

Drawing from the notion that a moral dimension arises once at least one person invests an action with moral significance, we can state:

Actions and Outcomes

Let A∈ {Discard, Store, Donate}

Let B be the resulting outcome (e.g., “food wasted,” “leftovers preserved,” “someone in need fed”).

Assessors

Let O={ X,Y }. (We can extend this to more observers if desired.)

Influence and Perception

Each observer oi ∈ O has an influence factor wi (their power or social clout) and a perception pi(B) (how strongly they believe outcome B is morally charged).

Moral Weight Formula

If M(A,B,O)≥T, a threshold of moral relevance, then A is deemed morally significant (moral or immoral).

If M(A,B,O)<T, it remains ethically neutral.

Propositional Statement

Define a proposition ϕ(A) “A is morally charged.” Then:If no one invests moral concern in leftover waste—i.e., if —then is false (morally neutral).

If Y strongly condemns food waste, we have . As soon as w becomes true and we call discarding “immoral,” or donating “moral,” etc.

In this way, the choice between discarding, storing, or donating leftovers joins the continuum of decisions that, under certain social or personal lenses, become ethically evaluated. This underscores a core idea: morality does not reside in the act itself but in the interplay between what is done, how it is perceived, and the incentives or repercussions that perception creates.

Conclusion

The central claim throughout is that morality lacks a single, transcendent anchor and instead crystallizes whenever one or more assesors call a choice right or wrong. Under the framework of omnimoral subjectivism, any act can assume moral weight the moment it attracts moral scrutiny, yet no code or command remains universally binding across all contexts. In this sense, moral laws do not descend from a realm of objective truth; they emerge out of particular vantage points shaped by culture, emotion, and power.

Key lines of reasoning support this view. Genealogical critiques peel back the seeming inevitability of moral standards, revealing how they are tied to human interests rather than timeless principles. Cross-cultural examples uncover values that clash from place to place, suggesting that any “universal” claim is ultimately local once you dig beneath the surface. Meanwhile, a game-theoretic lens underscores how incentives can shift moral boundaries, as what counts as a grave sin in one moment might pass unnoticed in another if no one labels it as such. Taken together, these perspectives show that moral frameworks are dynamic and negotiated.

This emphasis on subjectivity does not dilute the seriousness of ethics. Indeed, recognizing that moral pronouncements require active participation heightens our awareness of who wields the power to define right and wrong in any given setting. Rather than guaranteeing moral chaos, omnimoral subjectivism reveals the deeply human origins of our codes, inviting us to remain alert to how swiftly they may be reinvented or turned to new ends.

A final insight follows from this perspective. If an action becomes “moral” the instant someone invests it with that label, then each of us bears responsibility not just for our choices, but for the moral lenses we adopt or reject. Omnimoral subjectivism, therefore, is a reminder that the boundaries of right and wrong are as expansive or as narrow as the collective imagination and conviction behind them. Such a realization invites us to see morality as an evolving collaboration, one that gains its force from the participants who continually refashion it in response to changing circumstances, beliefs, and needs.